|

|

| Line 39: |

Line 39: |

| | | | |

| | === Images === | | === Images === |

| − | * [http://peir.path.uab.edu/library/index.php?/tags/177-hemochromatosis PEIR Digital Library: Hemochromatosis Images] | + | * [{{SERVER}}/library/index.php?/tags/177-hemochromatosis PEIR Digital Library: Hemochromatosis Images] |

| | * [http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/LIVEHTML/LIVERIDX.html#3 WebPath: Hepatic Pigmentary Disorders] | | * [http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/LIVEHTML/LIVERIDX.html#3 WebPath: Hepatic Pigmentary Disorders] |

| | * [http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/CINJHTML/CINJIDX.html#5 WebPath: Cellular Accumulations] | | * [http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/CINJHTML/CINJIDX.html#5 WebPath: Cellular Accumulations] |

Revision as of 01:33, 30 August 2013

Clinical Summary[edit]

This 61-year-old female was first admitted to the hospital because of ascites and pedal edema. A liver biopsy revealed a marked intracellular accumulation of iron. The serum iron concentration was reported as 220 mcg/dL. On the basis of these studies, the diagnosis of hemochromatosis was made. It should be noted that the patient also exhibited an abnormal glucose tolerance test at this time (following the ingestion of a test dose of glucose, the blood glucose level rose to 290 mg/dL at one hour and remained at this level for the next three hours). Subsequent to the first admission, the patient was admitted on several occasions for ascites. The patient's last admission was necessitated by the development of symptoms and signs of hepatic failure (hepatic coma) characterized by jaundice and coma.

Autopsy Findings[edit]

The liver weighed 820 grams. The cut surface was described as golden-brown in color, having a fine, diffuse nodularity, and being extremely firm in consistency.

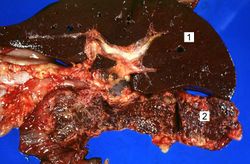

This is a gross photograph of liver (1) and pancreas (2) from this case of hemochromatosis. Note that both of these organs have a dark brown coloration.

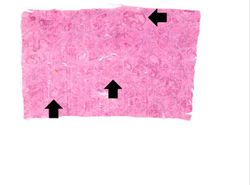

This is a gross photograph of a cut section of liver from this case of hemochromatosis. Note that the liver is dark brown. Although hard to appreciate in a photograph, the tissue is also firm (cirrhotic).

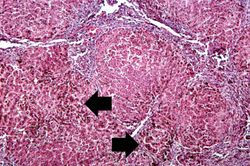

This is a low-power micrograph of liver from this patient. Note the nodularity of the tissue (arrows).

This higher-power view of liver from this case demonstrates the nodules and the brown/black pigment within liver parenchymal cells (arrows).

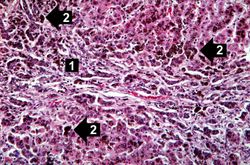

This higher-power photomicrograph demonstrates the increased fibrosis in the periportal area (1) and the pigment accumulation (2).

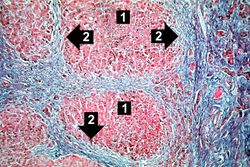

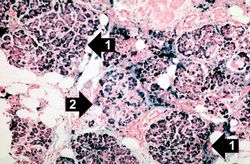

This trichrome stain of liver section demonstrates the increased fibrous connective tissue in this liver. Note that the liver nodules (1) are surrounded by fibrous connective tissue (2).

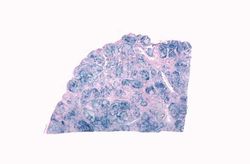

This is a low-power view of liver section stained with Prussian blue. Prussian blue reacts with iron in the tissue to give a blue color.

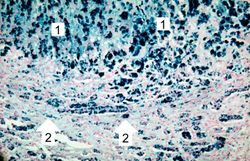

This higher-power view of liver stained with Prussian blue demonstrates the marked accumulation of iron within the parenchymal cells (1) and in the Kupffer cells in the periportal area (2).

This is a gross picture of pancreas from this case. Note the brown discoloration of the tissue.

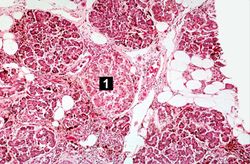

This is a histologic section of pancreas from this case. It is difficult to appreciate at this magnification, but there is brown pigment in the pancreatic acinar cells. Note the islets of Langerhans (1).

This is a histologic section of pancreas from this case stained for iron (Prussian blue). Note the accumulation of iron in the parenchymal cells (1). There is also iron in the pancreatic islets (2).

Study Questions[edit]

Diabetes mellitus, skin pigmentation, and hepatic fibrosis.

Primary or idiopathic hemochromatosis (also called hereditary hemochromatosis - HHC) is an autosomal recessive heritable disorder. The hemochromatosis gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 6, and the associated HLA haplotypes include A3 in 70% of hemochromatosis patients with fewer numbers of patients expressing B7, B14, or Bw35. Males are affected more than females (5 to 7:1) but this earlier and more severe clinical presentation in males is partly due to physiologic iron loss (menstruation, pregnancy) in females which delays iron accumulation. Even though the gene has been isolated and many aspects of the disease are known; the exact mechanism responsible for iron overload in primary hemochromatosis is not known.

The second type of hemochromatosis where the source of iron overload can be explained is called secondary hemochromatosis. Severe anemias due to ineffective erythropoiesis are the most common causes of secondary hemochromatosis. In these anemias the excess iron accumulation results from transfusions and also from compensatory increases in iron absorption. Alcoholic liver disease is also associated with increased iron accumulation in liver cells. Other more obtuse causes of iron overload leading to secondary hemochromatosis include: transfusions of packed RBCs, iron-dextran injections, and long term hemodialysis.

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder which results in increased iron absorption and iron induced parenchymal tissue damage. The exact mechanism of this functional defect is unknown. The iron overload leads to ferritin and hemosiderin in the parenchymal tissues of the body; primarily the liver, pancreas, myocardium, endocrine glands, and joints. Iron is a direct hepatotoxin and results in micronodular cirrhosis. Tissue damage and fibrosis is also evident in the pancreas, heart, and endocrine organs. The "bronze diabetes" of hemochromatosis is produced by excess melanin in the skin and by accumulation of hemosiderin in the dermal appendages. The diabetes is caused by destruction of pancreatic islets. Hemosiderin in the joint synovial lining leads to acute synovitis.

Wilson's Disease is also an autosomal recessive disorder that results in the accumulation of toxic levels of copper. Like hemochromatosis, the gene defect has been localized but the exact nature of the genetic defect is unknown. In this disorder, copper absorption and transport to the liver are normal; however, the copper does not get back into the circulation as ceruloplasmin and copper excretion into bile is severely impaired. The accumulation of copper leads primarily to liver, brain and eye damage. The liver develops fatty change and nuclear vacuolization in the setting of acute or chronic hepatitis which later progresses to cirrhosis. Neurologic manifestations include toxic neuronal injury primarily in the basal ganglia. Accumulation of copper in the cornea results in the formation of Kayser-Fleischer rings.

Additional Resources[edit]

Reference[edit]

Journal Articles[edit]

Related IPLab Cases[edit]